Health

Responding to North Carolina’s Behavioral Health Workforce Crisis

October 3, 2023

by Brianna Lombardi and Paul Lanier

North Carolina is experiencing a behavioral health service crisis. The need for services to prevent and treat mental health and substance use disorders has surged in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Across multiple demographic and age groups, depression, anxiety, and opioid use disorders increased since the onset of the pandemic. This crisis may be most evident for North Carolina’s youth. For example, 14.2% of youth in North Carolina reported a severe major depressive episode in 2022, and youth suicide rates in North Carolina reached an unprecedented level in 2021.

Meanwhile, the chronic shortage of trained behavioral health practitioners who can meet the needs of diverse communities of North Carolina has left many without the help they need. Almost 4 million people, or about 2 in 5 North Carolinians, live in a mental health professional shortage area. More than 50% of both children and adults who want to access behavioral health care are unable to do so. Many behavioral health services rely on trained professionals to work directly with individuals and families. Because of this workforce shortage, effective and potentially life-saving treatments are not reaching those who desperately need them.

To effectively respond to the behavioral health crisis in North Carolina, a well-prepared behavioral health workforce is essential. UNC is critical to this work not only for its role in educating future behavioral health professionals, but also as the home to many leading experts researching the state of the behavioral health workforce.

How the Behavioral Health Workforce is Organized

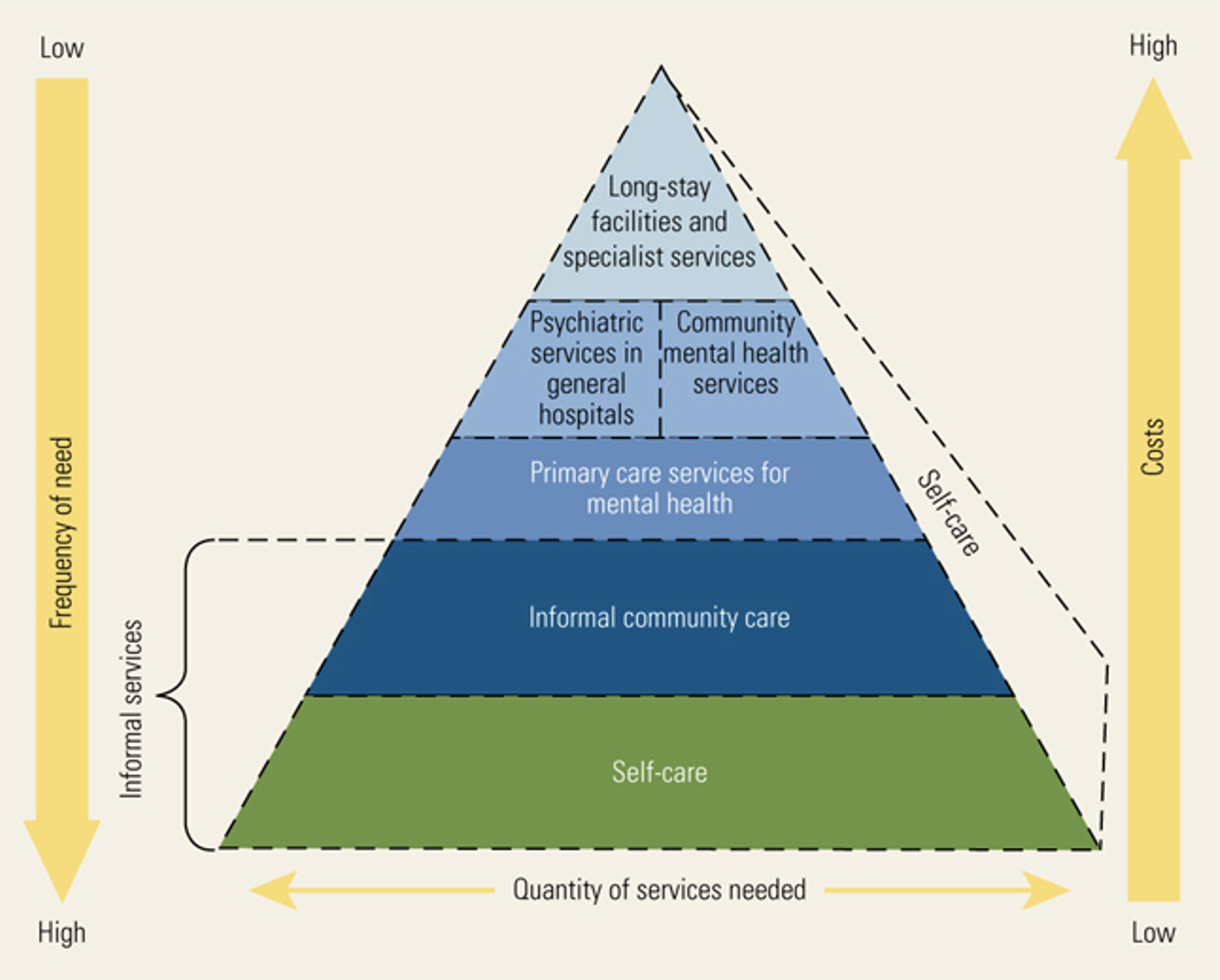

Historically, the behavioral health system was seen as separate from the physical healthcare system. We know now that the mind and the body are inseparable, and efforts to fully integrate behavioral health services within the broader healthcare system have taken off. Like other sectors of the healthcare system, the behavioral health workforce in North Carolina is diverse and includes an interdisciplinary group professionals and paraprofessionals working across community, residential, and hospital-based settings. The behavioral health workforce can be organized and understood in several ways.

North Carolina’s Behavioral Health Workforce Challenges

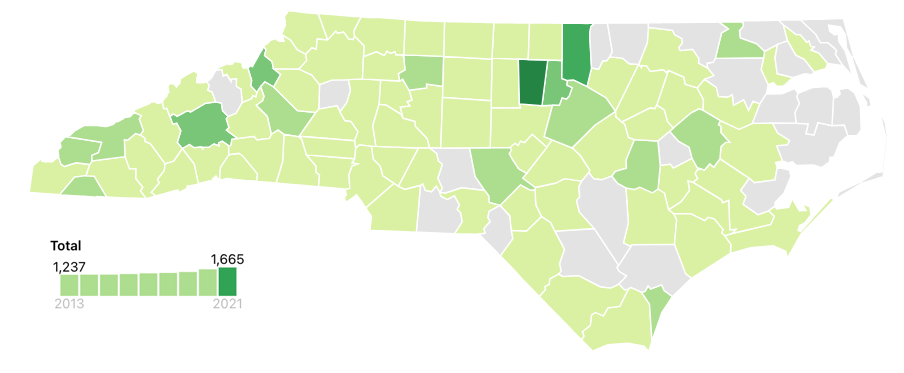

Experts at UNC are currently tracking the health and behavioral health workforce in North Carolina via the Program on Health Workforce at the Cecil G. Sheps Health Services Research Center’s Health Professions Data System. You can learn more about the Sheps Center and view our behavioral health workforce data here.

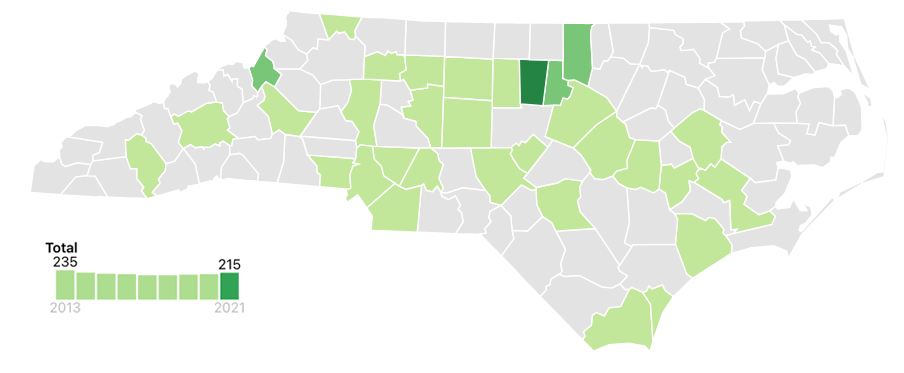

The data we have available shows us that like many valuable resources, behavioral health providers are not distributed equally in North Carolina. Although North Carolina is ranked 27th nationally for psychiatrists per the population, 22 counties have no practicing psychiatrists, with the average number of psychiatrists being worst in North Carolina’s rural counties. In metro areas, there are 1.79 psychiatrists per 10,000 people, while in rural counties there are 0.58 per 10,00 people.

Psychiatrists, per 10,000 People, 2021

Source: Sheps Health Workforce NC

Unfortunately, the picture is even worse when examining the availability of child and adolescent psychiatrists. More than 68 counties have no child and adolescent psychiatrist available. There are 0.24 child and adolescent psychiatrists per 10,000 people in metro areas as compared to 0.04 child and adolescent psychiatrists in rural areas.

Child or Adolescent Psychiatrists, per 10,000 People, 2021

Source: Sheps Health Workforce NC

Along with the limited supply of behavioral health professionals in the state, there is a considerable lack of behavioral health clinicians that represent the from racial and ethnic diversity of our state. We know that the diversity of the health workforce is important in increasing quality of health care, generally, but it may be even more relevant for increasing access to care for behavioral health. Nationally, about 84% of psychologists are White, less than 5% of all psychologists were Black, and 4% Asian. In North Carolina, about 6% about of psychologists are from underrepresented minority backgrounds. The lack of a behavioral health workforce that reflects the community it serves is an additional barrier to increasing access to behavioral health treatment.

Growing the Behavioral Health Workforce

The limited number of specialty behavioral health providers across all NC has made it necessary to adapt in other ways. Other health professionals, like primary care providers and pediatricians, can be trained to deliver behavioral health care. The delivery of care via tele-behavioral health and other virtual models is another option.

Because of the growing awareness of the importance of behavioral health and the critical need to grow the behavioral health workforce, educators at UNC are actively working to tackle this crisis. Here are just a few examples:

In addition to these preexisting efforts, the Carolina Across 100 initiative has identified behavioral health and suicide prevention as the focus of its program Our State, Our Wellbeing. Through this program, communities across North Carolina will work to address challenges facing our mental and behavioral health systems and contributing to suicide deaths.

Together, these partners — on campus and beyond — can move the needle in behavioral health outcomes and increase much-needed access to care for the state.

Carolina Across 100 is a five-year initiative charged by Chancellor Guskiewicz and housed at the School of Government’s ncIMPACT Initiative. This pan-University effort, guided by the Carolina Engagement Council, will form meaningful partnerships with communities in all 100 North Carolina counties to respond to challenges stemming from or exacerbated by COVID-19.